Introduction

Please work through this guide at your own pace - there is no time limit. Click on the ‘Next’ and ‘Previous’ buttons to navigate through the pages.

Throughout the guide there will be exercises where you will be able to type in your answers. Once the page is complete you will have the option to print out your answers, or to download them as a PDF file, for future reference.

These are the thoughts of two people who are depressed:

“I feel so alone, I will never see my friends again, I guess they have dropped me. They probably don’t like me – who would? There is no point in making any effort. It doesn’t pay off… I just hate myself”.

“I feel like crying all the time, but I feel I must hide it from others. I am so tired and can’t get interested in anything, or keep my mind on things I should be doing. I can’t even do basic things that seem so easy to other people…”

You may have had similar thoughts yourself.

Depression is a very common problem and many people feel low or down in the dumps at times. This is often due to life stresses such as bereavement, money or housing problems or difficulties in relationships.

Being sentenced and sent to prison is also stressful so not surprisingly depression is very often a problem for people in prison.

How can this guide help me?

It may seem that nothing can be done to help you feel better if you are in prison. You may not know who to turn to. But there are things that you can do that may help. There is also further help you can get if the depression does not seem to be getting better. It is important to keep hopeful. Most people who have depression do get better.

This guide aims to help you cope with depression and begin to get better. It is written by psychologists and people who have experienced prison. It aims to help you understand depression and to offer some practical ways to help you cope.

There is a lot of information in this guide and it may be helpful to read it several times, or to read it a bit at a time, to get the most from it.

We suggest you write things down in this guide to help you begin to understand and begin to deal with depression practically. Sometimes stopping and thinking can make things clearer, as can writing things down. Talking to someone you trust can help too. This might be a friend, listener or a PID worker or someone from the mental health team.

Some areas that can lead to people feeling depressed in prison are:

- Remembering illegal acts and reliving crime with guilt and regret.

- Prison itself with restricted space and activity.

- Missing friends and family, feeling lonely and isolated.

- Worrying about the future

- Living with other prisoners who may be violent and worrying about being at risk.

If you believe that you are in real danger of harm in prison please tell a member of staff about this. An officer or a member of healthcare or Prison Listener will help you.

What we know about depression

Life is sometimes difficult and, as mentioned things such as debt, divorce, relationship problems, loss of work and other hard things to deal with can make people more likely to become depressed. We now know that the way we think can also play an important role in depression.

The way a person thinks when they are depressed is very different from how they think when not depressed. Perhaps you can see some examples of depressed thinking in yourself or in someone you know who has depression. For example, someone may think they are useless or that things will never get better.

When thoughts begin to change like this, other changes also happen. Changes in thoughts, feelings, behaviours and in your body are all part of depression.

These are some of the signs or symptoms that you may experience if you are depressed

If you have ticked many of these boxes then you may be experiencing low mood or depression. When you’re depressed you may believe that you’re helpless and alone in the world; you often blame yourself for all the faults that you think you have. At the bottom of all this you feel bad about yourself, about the world and about the future. So you tend to lose interest in what’s going on around you and you don’t get any satisfaction out of the things you used to enjoy. It can become hard to make decisions or to carry out little tasks that you once did with no problem at all.

A physical health problem, misuse of substances or a history of sleep problems are known to affect depression (please consult your doctor or healthcare nurse if you think any of these may apply to you).

Summary

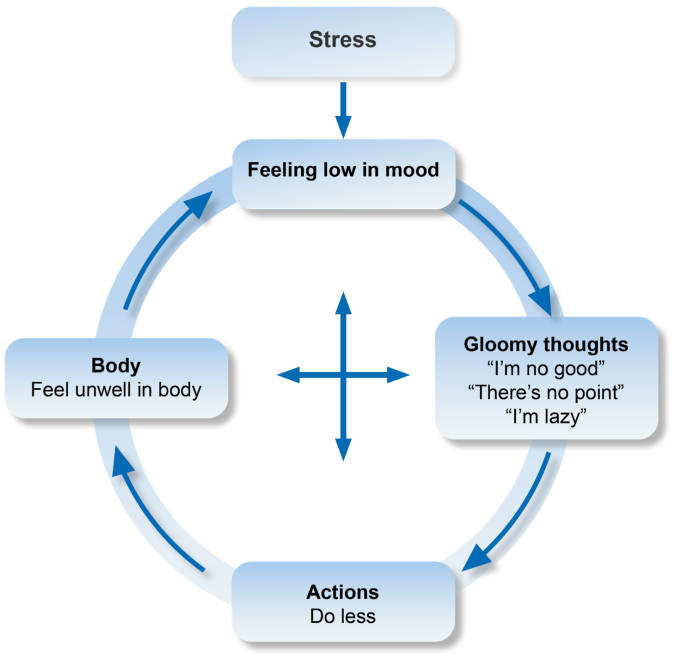

Stressful situations can lead to depression. When someone is depressed there are usually changes in the way they think, feel, behave and in their body’s reactions. Gloomy thoughts play an important part in depression.

How can I understand these feelings?

The way you think about things affects the way you feel, which affects the way you behave. It is difficult to change the way you feel, but you can change the way you think.

When you are feeling depressed you might have gloomy thoughts a lot of the time. With each negative thought the feelings of depression are likely to increase.

Sometimes negative thoughts can stop you from doing the things that you would normally do (for example “I can’t be bothered, there is no point”). As a result, you may have critical thoughts which make you feel even worse. In other words, you get caught up in a negative circle.

For example:

Suppose you are walking into the exercise yard and you see a friend who appears to ignore you completely. You might wonder why he has turned against you and this makes you feel upset.

Later on, you mention the incident to your friend, who tells you that he was worried about a problem of his own at the time and didn’t even notice you. This explanation should normally make you feel better and put what happened out of your mind. But if you’re depressed, you probably believe he really has rejected you. You might not even talk to your friend which makes things worse. If you’re feeling depressed you’re more likely to make mistakes like this over and over again. It can be like a roundabout you can’t get off, a negative circle. It can look a bit like this:

Each part seems to make other parts worse.

Can I recognise these gloomy thoughts?

When you are feeling low the gloomy thoughts may be so familiar and happen so often to you that you just accept them as fact.

Gloomy thoughts are often about yourself for example:

“I’m no good”

“People don’t like me“

“I’m a bad mixer”

“I look ugly”

These thoughts are sometimes about other things such as the world around you or the future. For example:

“People are unkind”

“The world is a horrible place!

“Nothing will work out well”

What more should I know about these gloomy negative thoughts?

We have given examples of the negative thoughts people have when they are depressed. It is important to remember that you might still occasionally have some of these sorts of thoughts when you are not depressed. The difference is that you would generally ignore them. When you are depressed, however, these thoughts are around all the time and are hard to ignore.

Let’s look at these negative thoughts in more detail:

- Negative thoughts tend to just pop into your mind. They are not actually arrived at on the basis of reason and logic, they just seem to happen.

- Often the thoughts are unreasonable and unrealistic. They serve no purpose. All they do is make you feel bad and they get in the way of what you really want out of life. If you think about them carefully, you will probably find that you have jumped to a conclusion which is not necessarily correct. For example, thinking someone doesn’t like you because they don’t smile at you or acknowledge you.

- Even though these thoughts are unreasonable they probably seem reasonable and correct to you at the time.

- The more you believe and accept negative thoughts, the worse you are likely to feel. If you allow yourself to get into the grip of these thoughts, you find you are viewing everything in a negative way.

As we have said, when people become depressed, their thinking often changes. You make some of the following thinking errors when you are depressed:

This means you think things are much worse than they really are.

For example, you make a small mistake at work and fear that you may be disciplined because of it. In other words, you jump to a gloomy conclusion and believe that it is likely to happen. Or you may spend a long time worrying that you have upset a friend only to find later he or she couldn’t even remember the comment.

For example, if one person doesn’t get on with you, you may think, “no one likes me”. If one of your many daily tasks hasn’t been finished, you think, “I’ve achieved nothing – nothing has been done”.

In other words from one thing that has happened to you, you wrongly jump to a conclusion which is much bigger and covers all sorts of things.

People who are depressed tend to focus their thinking on negative or bad events and ignore positive or good events. You might have played a game of pool and missed one easy shot, but played well in general. After the game, you just think about that one missed shot and not the others that you played well. You may have many good friends who you have known for years, but you concentrate and worry about one that has fallen out with you rather than remembering all the other good friends.

Often if our mood is low we blame ourselves for anything which goes wrong, even if things have nothing to do with us in reality.

For example, a prison officer appears to be off-hand with you - your automatic thought is “he’s got it in for me… what have I done?” But it is more likely that he’s tired or has had a bad day himself. In this example, you have taken the blame personally. You may also be self-critical and put yourself down with thoughts such as “I am an idiot”, “I never get things right”.

Sometimes we think we know what others are thinking and if our mood is low we expect it to be bad. For example if your cell mate is quiet you may think “that’s because he doesn’t like me”. It is worth remembering that many people in prison are stressed and anxious. This may be the reason why sometimes people act as they do.

Summary

When people are depressed, they often have gloomy or unhelpful thoughts about themselves, others, the world and the future. They can also make errors in the way they think. They exaggerate the negative, over-generalise bad events, ignore positives in their lives and can take things personally. It is important to uncover gloomy thoughts and errors in thinking.

How can I help myself?

So far we have talked about how what we think affects the way we feel. We have looked at some ways of thinking which can make depression worse. In this section, we look at practical steps to help to overcome depressive feelings, thoughts and behaviours. Even though at first these steps appear difficult, it is worth making the effort in order to get through what feels like a very difficult time.

• Mix with people

• Take exercise

• List things to do

• Join in activities

• Do things you enjoy

When people are depressed they often don’t feel like doing anything, find it hard to decide what to do each day and can end up doing very little. When you are in prison, it can seem at first that it is difficult to plan your own time. But many people in prison still manage to make a daily plan to give structure to their lives. Making your own structure within the prison regime is important.

Begin by making a list of things to do. The things to do can be as simple as spending a little time doing exercises, such as sit-ups or press-ups. Then plan out an action list, start off with the easiest task at first and don’t aim too high. It might be useful to take a sheet of paper and write the days of the week and the times, as shown. Exercise has been shown to make people in prison feel less depressed.

You can then write down what you plan, and tick off what you’ve done. At the end of each day you’ll be able to look back and see what you’ve achieved. Physical exercise and activity can really help to lift your mood. Try and build a little in each day. Mixing with others can also help, especially if they have a positive outlook. Keeping active can help the time pass much more quickly. It is the best way to fight depression if you are in prison.

Here is a list of activities tried by other prisoners:

• reading

• exercise in cell or gym if available

• learning yoga or mindfulness

• taking part in education or work

• creative writing etc.

• taking part in association

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | Sunday | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9am | |||||||

| 11am | |||||||

| 1pm | |||||||

| 3pm | |||||||

| 5pm | |||||||

| 7pm |

When people are depressed they often forget what they’ve achieved and what they enjoy. Most people have more things going for them than they are usually aware of. When you have started to keep an action plan, look back over what you have done and put a P next to those which have given you pleasure and an A next to those activities where you felt you achieved something and did well.

Try not to be too modest: people who are depressed tend not to take credit for their achievements. Try and build some pleasant events into your day. Each day treat yourself, perhaps order something extra from your kiosk, a period of listening to music or to enjoying a television or radio programme.

If you make the effort to achieve something it will feel good if you reward yourself afterwards.

Most people who are depressed think their lives are so awful that they have every right to feel sad. In fact, our feelings come from what we think about and how we make sense of what has happened to us.

Try to think about a recent event which had upset and depressed you. You should be able to sort out three parts of it:

A. The event

B. Your thoughts about it

C. Your feelings about it

Most people are normally only aware of A and C. Let’s look at an example.

Suppose someone criticises you for something you have done.

A. The event – criticism

to

C. Your feelings – hurt, embarrassed.

But what was B!… your thoughts? What were you thinking?

Let’s imagine it was “He thinks I’m no good, and he’s right I’m hopeless”.

How depressing! No wonder you feel bad! It isn’t always obvious what the thoughts are but it is important to become aware of these three stages A, B and C as if we can change what we think about an event we may be able to change how we feel about it.

A useful technique to try is called balancing. When you have a negative, critical thought, balance it out by making a more positive statement to yourself. For example:

The thought: “I’m no good at anything”, could be balanced with: “my friend said how much she missed me when she visited yesterday”.

Another thing you could do is write down your negative automatic thoughts in one column – and, opposite each one, write down a more balanced positive thought. Like this:

| Negative automatic thought | Balancing thoughts |

|---|---|

| John doesn’t like me; he ignored me today. | He may be just having a bad day himself. Maybe he’s had bad news. |

The person who is depressed doesn’t remember details of events but tends to think in general statements, such as “I’ve never been any good at anything”. Try and train yourself to remember details so that good times and experiences are easy to recall. Think of particular examples, rather than in general.

A daily diary can help you to do this. Make lists of actual achievements and good aspects of yourself such as “I’m always on time”, “I helped my friend on Tuesday”, “I’m a good listener”, “I really care for my family”.

Try to keep a diary of events, feelings and thought. It may look a bit like the following table. Use the approaches described to gain more balanced thoughts. Look out for errors in thinking.

| Event | Feeling or emotion | Thoughts in your mind | Other more balanced thoughts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Example | |||

| People were laughing when I entered the room | Low, depressed, angry | They think I’m stupid |

I’m taking this too personally, this may be nothing to do with me. There may have been some joke they were sharing. |

In summary

Using a daily plan, pleasure and achievement notes and keeping a diary of automatic thoughts and more balanced thoughts can help you to fight depression and the gloomy thoughts that go with it.

Sometimes we feel overwhelmed by the very complicated and difficult things we have to do. One thing which helps with this sort of problem is to write down each of the steps which you have to take in order to complete the job – then tackle one step at a time.

Problem solving can seem more difficult when you feel depressed. If you have a particular difficult problem, try and look back to times when you may have successfully solved similar problems and use the same approach. Or ask a friend (or Listener) what they would do in a similar situation. Be clear. Write down all your possible options everything you can think of, even apparently silly solutions choose the best approach.

Sometimes when people are depressed they start doing things to try and feel better that are really quite unhelpful. For example: drinking alcohol (hooch), staying in bed, binge eating, zoning out in front of the TV. By noting everything you do in your daily plan, you can start to see patterns of what helps and what makes you feel worse. So it might be a case of increasing some behaviours and reducing others.

Sometimes people have long held views about themselves that are very self-critical – for example, “I’m not a very clever person” or “I’m not a very lovable person”. These beliefs are often because of our past experience and may hold no truth in present reality. Try to challenge this criticism, stop knocking yourself down and look for evidence that disproves the beliefs. What would you say to a good friend if they held that belief about themselves?

Many people experience a difficult time in their lives that is linked with events that they cannot change. For example, a bereavement or several bereavements over a short period, imprisonment, longstanding illness, chronic financial problems or isolation. Sometimes several of these events happen together and depression can result. In time, most people bounce back, but it may be hard to do this without help.

Sometimes no matter how hard we try, our thoughts will not be changed. If you find yourself getting in to endless arguments with your thoughts, this can then become part of the problem. You may start to feel useless for not being able to challenge your thoughts well enough and before you know it there are a whole host of more negative, self-critical thoughts in your mind. This can be the case particularly if you have had a few bouts of depression.

A slightly different approach to managing depression. Mindfulness is a form of meditation that involves being totally in the present moment. It involves observing what is happening with a calm, non-judging awareness, allowing thoughts and feelings to come and go without getting caught up in them. The aim is to concentrate only on what is happening in the here and now, not the past and not the future. We know that worrying about the past and the future is a major problem for depressed people. Studies in prisons show that practicing mindfulness can help reduce depression and stress.

The following mindful breathing exercise may be useful:

- Find a quiet space where you won’t be disturbed. Sit comfortably, with your eyes closed or lowered and your back straight.

- Bring your attention to your breathing.

- Notice the natural, gentle rhythm of your breathing as you breathe in and out, and focus only on this.

- Thoughts will come into your mind, and that’s okay, because that’s just what the mind does. Just notice those thoughts, then bring your attention back to your breathing.

- You may notice sounds, physical feelings, and emotions, but again, just bring your attention back to your breathing.

- Don’t follow those thoughts or feelings, don’t judge yourself for having them, or analyse them in any way. It’s okay for the thoughts and feelings to be there. Just notice them, and let them drift on by; bringing your attention back to your breathing.

- Whenever you notice that your attention has drifted off and is becoming caught up in thoughts or feelings, simply note this has happened, and then gently bring your attention back to your breathing.

- Thoughts will enter your awareness, and your attention will follow them. No matter how many times this happens, just keep bringing your attention back to your breathing. If you are very distracted it might help to say ‘in’ and ‘out’ as you breathe.

The more you can practice this exercise the more it will help you to manage your depression. At least 15 -20 minutes a day is recommended. Many prisons have similar practice through the Phoenix Trust, you may be able to attend one of their sessions.

Yoga is known to help to manage depression for people who are in prison, ask your prison librarian if you would like to find out more about yoga or mindfulness. A member of the mental health team may also be able to help you with this.

Antidepressants are sometimes prescribed by the doctor in healthcare or psychiatrist. They have been shown to be helpful for many people suffering from depression. Antidepressants work on the chemicals in the brain to make you feel less depressed. They are not addictive and once you begin to feel better, usually after quite a few months, you can plan, with your doctor, to stop taking them. This should not cause you any difficulty and your doctor will gradually reduce the dose.

When you begin a course of antidepressants it is important to remember that they do not work immediately. It will take 2-4 weeks before they take effect and you need to keep taking them regularly to feel the benefit. They can have some side effects at first but these are usually quite mild and will generally wear off as treatment continues. Your doctor or nurse will advise you about this. Although people often start to feel better within 2-4 weeks of taking antidepressants, it is important to keep taking them for as long as your doctor advises. This helps stop the depression coming back.

Further help

We hope you will use the exercises suggested in this guide. They should help you begin to overcome your depression and get back control over your thoughts and your life.

If you feel that you are making little progress, then other help is available to aid you in overcoming your problem. Discuss this with your case officer or enquire at the Healthcare Centre if it is possible to see a counsellor, a nurse or to have contact with the Samaritans.

If you think that you are at risk of self-harming then please speak to a member of healthcare staff, a prison officer or a prison listener.

There are also guides in this series on:

• Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

• Anxiety

These guides are available at www.cntw.nhs.uk/selfhelp

Useful organisations

Useful organisations

- Combat Stress

Helpline: 0800 138 1619

Combat Stress, Tyrwhitt House, Oaklawn Road, Leatherhead, Surrey, KT22 0BX

The UK's leading military charity specialising in the care of Veterans' mental health. We treat conditions such as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), depression and anxiety disorders. Our services are free of charge to the Veteran. - Criminal Cases Review Commission

Tel: 0300 456 2669

23 Stephenson Street, Birmingham, B2 4BH

An independent body, set up under the Criminal Appeal Act 1995 to investigate the possible miscarriage of justice. - MIND

Tel: 0300 123 3393

Mind Infoline, PO Box 75225, London, E15 9FS

Working for a better life for people in mental distress, and campaigning for their rights. Helpline available Mon - Fri, 9am - 6pm. - NACRO

Helpline: 0300 123 1889

Walkden House, 16-17 Devonshire Square, London, EC2M 4SQ

Offers resettlement information, housing projects and employment training before and after release. - National Association of Citizens’ Advice Bureaux

Contact your local office who can direct you to local groups who can help. Offers advice, information or advocacy on a wide range of issues. - PACT – Prison Advice and Care Trust

Helpline: 0808 808 2003 (freephone)

29 Peckham Road, London, SE5 8UA

Provides a range of services to both prisoners and their families. - Partners of Prisoners and Families Support Groups (POPS)

Tel: 0161 702 1000

1079 Rochdale Road, Blackley, Manchester, M9 8AJ

Offers advice, information and moral support to anyone who has a loved one in prison. - Prison Fellowship (England & Wales)

Tel: 020 7799 2500

PO Box 68226, London, SW1P 9WR

Offers support to prisoners, families and ex-offenders. Although based on a Christian ethos services are offered regardless of belief. - Prison Phoenix Trust

Tel: 01865 512 521

PO Box 328, Oxford, OX2 7HF

Using meditation and yoga, the trust encourages prisoners to find personal freedom inside UK prisons by giving workshops and through correspondence. - Prison Reform Trust

Tel: 020 7251 5070

15 Northburgh Street, London, EC1V 0JR

Campaigns for better conditions in prison and the greater use of alternatives to custody. - Prisoners’ Advice Service

Advice line: 02072 533 373

PO Box 46199, London, EC1M 4XA

Takes up prisoners’ complaints about their treatment within the prison system. - Samaritans (There should be a freephone available on your wing)

Tel: 116 123

Post: Freepost SAMARITANS LETTERS

Provides confidential, emotional support to anyone in need. - National Sexual Health Helpline

Tel: 0300 123 7123

References

References

A full list of references is available on request by emailing pic

Rate this guide

Share your thoughts with other people and let them know what you think of this guide.

Acknowledgement

Written by Dr Lesley Maunder and Lorna Cameron, Consultant Clinical Psychologists.

Many thanks to Gail McGregor, Lead Consultant Psychologist/Approved Clinician, Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust, who has contributed to the review of this guide.

With thanks to prison listeners in Northumberland.

Published by Cumbria, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Foundation Trust

2024 Copyright PIC/133/0324 March 2024 V5

Review date 2027

Print or download as a PDF

Print or download as a PDF